11 Encounters with square wheels

The first major hint that I had a scientific bent – and not just a fondness for natural history – occurred when I joined the Honors Program in Zoology at UC Berkeley. I joined mainly because an honors degree might enhance my odds of being admitted to medical school.

One of the requirements for honors was to take a seminar course with other honors students. A professor would help us pick a paper or set of papers to review and then present in the course seminar.

I worked with Professor William Lidicker, a small-mammal ecologist in the Museum of Vertebrate Zoology (UC Berkeley). Lidicker suggested I review some papers by Lee Kavanau, a professor at UCLA. In the early 1960s, Kavanau studied the behavior of mice – not domesticated white mice, but wild deer mice (Peromyscus). Kavanau was a creative biologist and was adept with electronics as well.

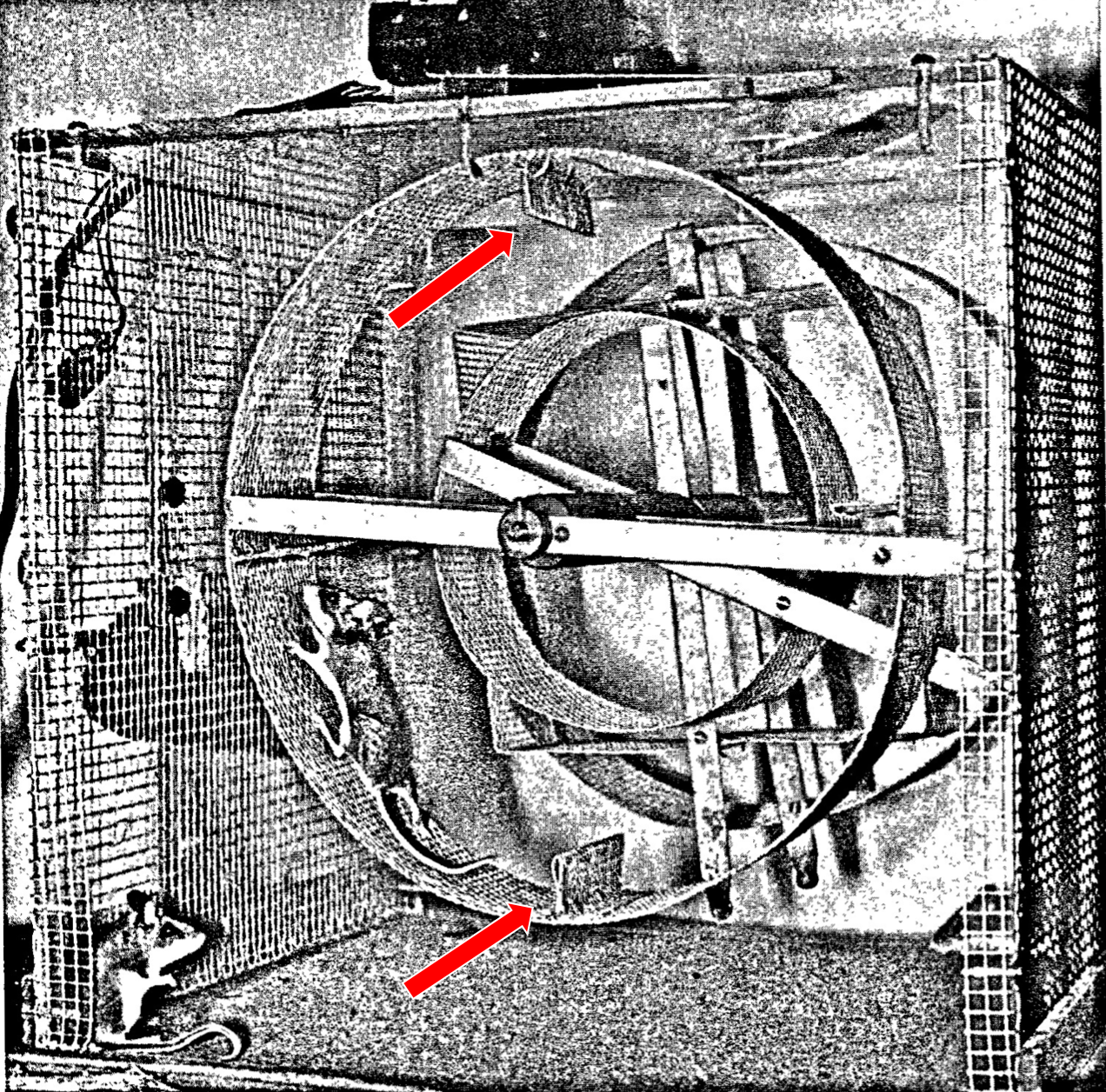

Kavanau and Brant (1964) caught my attention. They kept individual wild canyon mice (Peromyscus crinitus) in cages with four running wheels. [Wild mice, of course, are ‘born to run.’] Two wheels were large and round (one had a smooth floor, but the other had a mesh floor), a third wheel was small and round, and the fourth was small and square. Kavanau and Brant trained the mice to run on each of the four wheels and then let each mouse choose a wheel. The mice preferred the square wheel!

What! I had trouble understanding why mice would run at all, but I was flummoxed that they chose to run on a small square wheel, which would make running challenging – to put it mildly. Their choice made no sense to me. It didn’t fit.

Kavanau (1967) later did a variation, this time with one round and large wheel, one round and small wheel, and one large wheel with four hurdles (each 1.9 cm high), and one square wheel. He again trained the mice to run on these wheels and then let them choose. All six mice preferred either the round wheel with hurdles or the square wheel! None chose the standard round wheel.

Nothing I’d encountered to date was as perplexing as Kavanau’s findings. Why would mice always pick the ‘hardest’ wheels?

Kavanau (1967) himself was surprised but offered an explanation. Because wild canyon mice live in rocky areas, often with logs, boulders, or other obstacles, Kavanau proposed that “exercise in which quick reflex actions and split-second timing and coordination of movements play a large role is preferred to exercise in which vigorous muscular activity is the primary requirement.” Kavanau was guessing, but his guess struck me as interesting and plausible.

Looking back, I realize that reading Kavanau’s papers was a ‘pinball’ experience for me. His studies demonstrated that the results of experiments could sometimes be completely unpredictable – specifically, animals don’t always do what one logically expects. I later learned that this is known as The Harvard Law of Animal Behavior:

“Under precisely controlled experimental conditions, the animal reacts as it damn well pleases.”

For some people, unpredictability might make science unappealing. For me, it was a magnet. Sure, it is fun when you derive a hypothesis and conceive and executes an experiment that supports your hypothesis; but it can also be exciting when you find out that your motivating hypothesis was wrong. You immediately check to make sure you coded the data correctly. And IF you did code correctly, you have to (or get to!) try to figure out why your intuition and logic was wrong. What had you missed? That chase is exciting, if sometimes frustrating.

Kavanau’s work taught me two cruicial natural history lessons. First, design experiments relevant to the biology of the organisms under study. Second, study wild animals, not domesticated ones (Kavanau, 1964), at least if one is interested in exploring natural behaviors.

Around 2007 I visited UCLA and sought out Kavanau, who was by then an Emeritus Professor and about 84 years old. I told him that his papers had helped launch my research career. He was pleased, of course, but immediately started telling me about his new research on the evolution of sleep. Kavanau might have been old, but he remained excited about science and doing science. He was and is inspiring.

When working on this sketch, I searched online for “Lee Kavanau” and found his detailed autobiography. I recommend it – Kavanau had a remarkable and diverse career.

I shiver to think what my life would have been like if I’d gone into medicine. Several professors, Great Blue Herons, and square running wheels saved me from a lifetime of medical torment. The career I did choose presented plenty of enticing wheels with hurdles. I’ve never looked back or stopped running. I have no regrets.