6 Cake mixes, silver arrows, and The Chef

Encounters with staff at Deep Springs were a memorable part of the experience. For me, the times I spent with “The Chef” were important. But before I describe those experiences, I first need to skip back to when I was a Cub Scout and learned that cooking was fun.

6.1 An early motivation for becoming a cook

Many boys growing up in the 1950s avoided kitchens. However, I discovered kitchens and cooking when I was a Cub Scout (about 5 to 10 years of age). I confess that I was an ambitious Cub Scout. My goal was to earn as many ‘silver arrows’ (arrows were the Cub Scout equivalent of a merit badge of the Boy Scouts) as possible and then display them proudly on the front of my short-sleeve, blue uniform. The more arrows I earned, the better.

My Mom tolerated cooking and was never an accomplished cook. But she was interested in our health, so the family meals she served rarely included desserts.

As a neophyte Cub Scout, I discovered I could earn a silver arrow merely by cooking 10 new recipes. I immediately understood the appeal! Cooking 10 new things was much more fun than doing 10 good deeds (or whatever activities qualified for arrows in those days).

My Mom encouraged my cooking for silver arrows, even if this meant I was consuming an unhealthy excess of sweets. But for me, this was a win-win. With each cake, I earned 1/10th of an arrow, plus I got to have my cake and eat it too. Thus, I first learned about ‘gaming the system.’

The local grocery store had a variety of packaged cake mixes, each with suggested variations for icings. For example, I could buy three packages of chocolate cake mix and top each cake with a different icing: three packages times three icings = 3/10’s of a new arrow + 3 cakes to savor. Life was good.

At some point, my Mom offered to teach me how to make a cake from scratch. I tried it once but decided it was too much work. Eventually, I graduated to Boy Scouts. And yes, I did get a Boy Scout merit badge cooking, but I do not recall what I did to earn that one.

For years, I thought that I’d outsmarted my Mom on this one. But now I wonder whether she too had a sweet tooth and used me and my silver arrows to her own advantage. I’ll never know as she died before I thought of this alternative explanation.

6.2 Encounters with The Chef

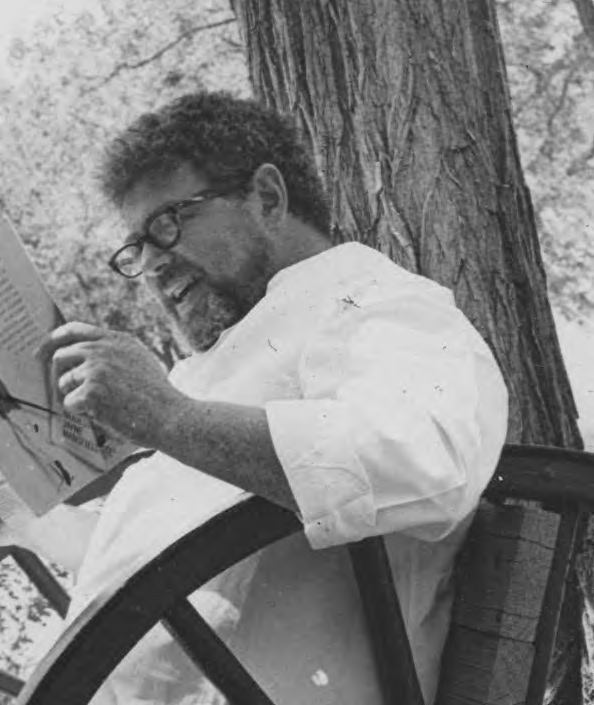

Let’s jump back to Deep Springs. Around 1963, Warren Jacober was hired as the cook for the College. Instantly known as ‘The Chef,’ he was undeniably charismatic. He was big, had sandy and un-combable hair and beard, and a well-earned pot belly. He lived in ripped-off chef’s trousers and sandals and often wrapped a red bandana jauntily around his neck. From a distance or from close-up, The Chef was a striking presence.

And he could cook. He’d trained in Europe and had worked at prestigious restaurants in New York (Lindy’s, The Four Seasons). He was a consummate, boisterous, and uninhibited showman. He’d worked in vaudeville, and it showed. I’ve never met anyone like him.

By a stroke of complete luck, my labor job when The Chef arrived was washing pots in the ‘boarding house’ (our dining hall and kitchen). I got to know him well, but our initial encounter was unpleasant for both of us. After he served us his very first breakfast at Deep Springs, I washed his omelet pans. When The Chef saw what I’d done, he was momentarily silent, but then he gently but firmly told me that his omelet pans had never been washed before and would never be washed again. Some lessons in life one learns instantly. Fortunately, The Chef didn’t hold a grudge. [Note: I purchased my own omelet pan in 1971 and have never washed it.]

We asked The Chef to give us cooking lessons, and was delighted to do so. Our first attempt was crêpes de la mer – crepes with a shrimp scampi sauce. He demonstrated how to make and cook crepe batter, but his crepes were beautifully round, flat, and thin, whereas ours were decidedly ‘none of the above.’ How did he do that? We were all using the same batter and pans, but we were obviously doing something(s) wrong. That day I learned an important lesson: a good recipe does not guarantee a good meal.

I often just watched him cook. He was a pro, and he loved the act and art of cooking. I grew to love cooking, and I still cook most days. I find it psychologically satisfying – as well as tasty. Why satisfying? Because I can complete a project each time I cook a meal, whereas in my scientific life, I can finish only a few projects even in a good year. Cooking an evening meal makes me feel like I’ve accomplished something that day. And I have.

We ate well during the months that The Chef lived at Deep Springs. Moreover, his meals were often ‘showtime.’ The most memorable example came when Hugo, one of the students in the class after mine, accidentally lopped of the tip of the middle finger while working with a jointer (a dangerous carpentry tool).

I drove Hugo to the nearest hospital, in Bishop (45 miles away). The attending doctor was delighted when he saw the geometry of Hugo’s amputated middle-finger. The cut was on a steep angle rather than crossways. All the doc had to do was bend the flap over and stitch it to the stub. No muss, no fuss [from my perspective, though not from Hugo’s].

Hugo’s ‘amputation’ occurred shortly before the Christmas holidays, and The Chef jumped on an opportunity for fun. He knew Hugo would be going home to spend the holiday with family and friends, who would no doubt ask how he lost the top joint of his middle finger.

The Chef promptly announced a contest for the best essay on how Hugo lost his fingertip. The Chef would then cook (for the entire student body and faculty) whatever the winner chose for a meal. Those were high ‘steaks’ indeed.

The Chef announced two categories of entries. One would be for a general (polite) audience (i.e., family), but the second would be for ‘male peers.’

Several Deep Springers submitted stories for the male-peer category, but none of us submitted an entry for the general audience one. I do not remember the details of the winning male-peer story (Lincoln Bergman wrote it), but the theme was – not surprisingly for an all-male college in the early ’60s – sexual in theme and decidedly gross. Lincoln rose to the occasion (as he always did).

The Chef stayed with us for most of a year and then moved on to a restaurant in Mammoth Lakes, a ski area in the eastern Sierras. While he and his family were there, his wife spotted a classified ad (possibly in The New Yorker?), submitted by an attorney searching for people named “Jacober.” A Jacober from back East had died intestate, and the attorney was searching for surviving relatives. Suddenly, The Chef inherited a fortune from an unknown relative.

He promptly left Mammoth and built a restaurant in Idyllwild, California, a small resort in the San Jacinto mountains above Palm Springs. I visited him there twice. The first time was in spring 1966, just after I returned from Costa Rica. He offered me a job, but this was during the Vietnam War. Had I taken that job, I would have been drafted in ‘short order.’ The second time was when one of my roommates from Berkeley and his spouse celebrated their wedding at The Chef’s restaurant The Chef in the Forest). The Chef cooked an entire tenderloin, among other delights. A great time was had by all.

The Chef was a consummate showman, and soon he was lured into television. In the mid-60s, he created a cooking show but had to commute to San Diego for filming. [Note: This was soon after Julia Child started filming “The French Chef” in Boston (1963).] On one of those trips (1968), a friend was driving, lost control, and rammed a power pole. The Chef was killed at age 41.

The world was suddenly and permanently a much poorer place. He “coulda been a contender.”