22 A lizard that mimics a beetle?

Early in my biological career. I thought about what I hoped to accomplish as a biologist. I wanted to describe a new species and to discover a new “Batesian” mimic (that is, a palatable species that fools potential predators into thinking that it is noxious, distasteful, or dangerous). I described several new species of Peruvian geckos during my first year in grad school (Chapter 13), and I discovered of a new mimic happened partway through the first Kalahari trip.

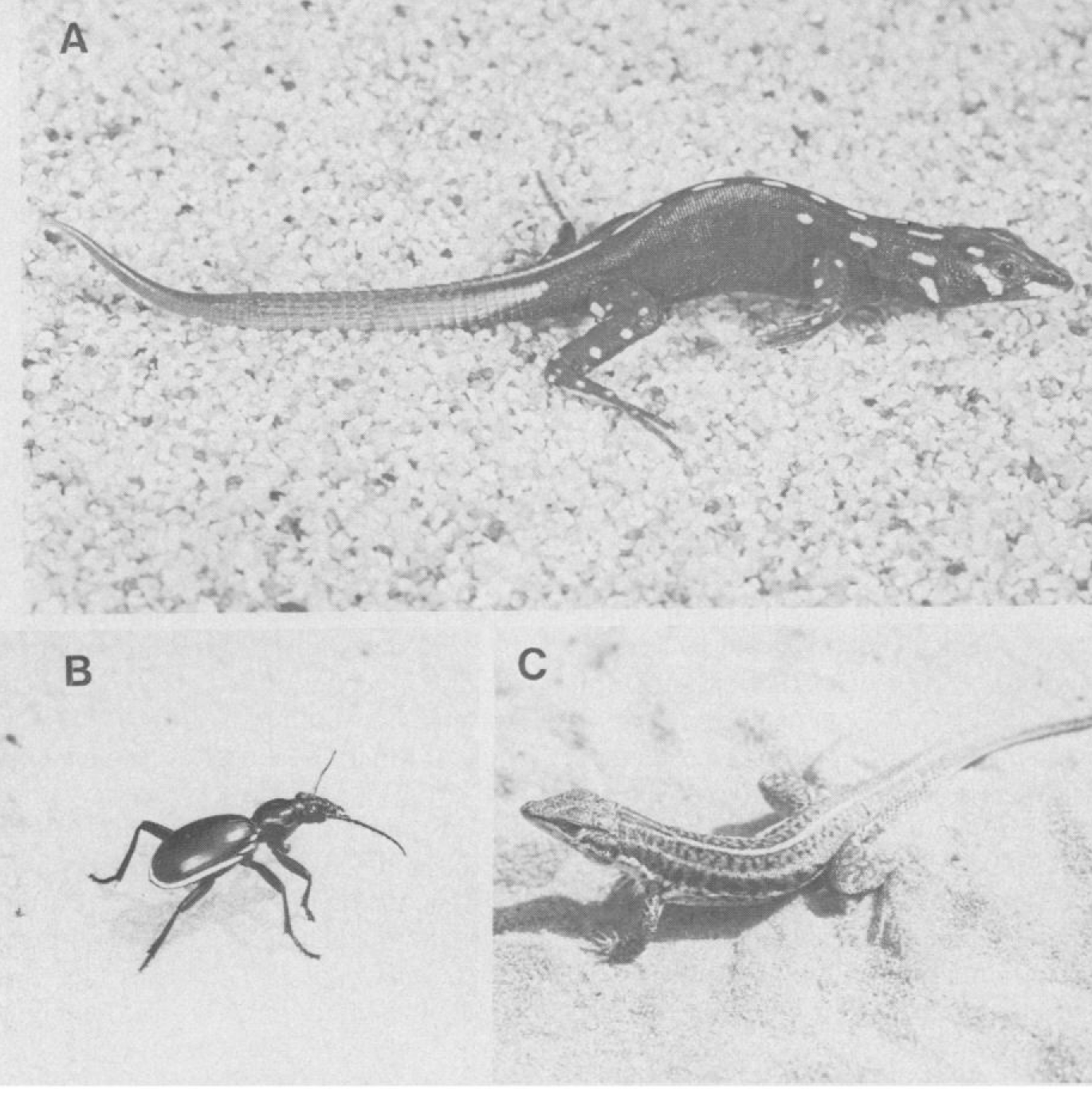

By early January we’d spent a month in the field and had already found most of the Kalahari species. But on 5 January, Larry and I spotted a baby lizard, which must have just hatched. Its body was jet black with broken white stripes on the flanks, and the lizard was blatantly conspicuous on the red Kalahari sands. Its tail was, however, was sand colored. Because we hadn’t seen a lizard like this before, we initially assumed (or hoped) we’d found a new species. We were disappointed when was a baby Heliobolus lugubris.

What surprised us was the way these baby lizards moved. Unlike the adults (and unlike all other lacertids), which walk with a side-to-side lateral undulation, these babies arched their backs, held their tails flat to the ground, and walked stiff-legged and jerkily. No other lizard walks that way.

Another black and white Probably from day one in the Kalahari, we’d been seeing a black-and-white carabid beetle (Anthia) that actively moved about during the day. Initially we paid little attention to them – after all, we were looking for lizards. In any case, black and white coloration is a classic “warning coloration” of many noxious animals (e.g., skunks, porcupines). Afrikaners call these beetles “oogpisters,” which euphemistically translates as “eye-squirter.” When confronted by a predator, oogpisters squirt a foul-smelling acidic stream (formic acid, tiglic acid, etc.). As far as I can tell, nothing eats oogpisters.

It didn’t take us long to realize that the baby lizards – while they remain within the size range of the beetles – are likely mimicking the beetles both in color and gait. Some insects are known to mimic vertebrates, but a vertebrate mimicking in insect was unheard of.

This example of mimicry was obvious to us, and we didn’t think much about it until we returned to the States. Once home, I started reading about known cases of mimicry. I soon realized that this mimicry – specifically, a lizard mimicking a beetle – was unique. But to make a case, we needed a good photography of a baby lizard walking.

With support from The National Geographic Society, we returned to the Kalahari for a few months (1975-6). We were unable to get good photos of the baby lizards (they are small and move quickly), but we brought home two babies that we would photograph in Berkeley. Carolyn and I stopped in Istanbul for a few days before flying to Seattle, where we cleared customs. To import live lizards, we needed approval from the Department of Agriculture. The agent asked to see our lizards. I carefully opened the container and was devastated to see two stiff and unmoving lizards – they must have frozen in the plane’s luggage compartment during the over-Arctic flight. I was crushed as I knew that our mimicry story would be difficult to publish without good photos of the arch-walking juveniles. The agent saw the pained expression on my face and said, “I’m so sorry.”

I repacked the dead lizards. Carolyn and I flew on to San Francisco and got back to our cottage in Berkeley late that night. I decided to put the carcasses into the freezer and pickle them the next morning. But when I opened the lid, two feisty babies scampered out. They hadn’t died but had just been very cold!

J. Hensel (Scientific Photographer, Department of Zoology) took some good photos for us, and we wrote a paper and published it in Science – my second paper in that journal! I thereby fulfilled my early goal of discovering a mimic (see above).

Over the decades our mimicry story has attracted attention. It is fun natural history, and you can watch these remarkable baby lizards beetle walking on a clip from David Attenborough. [Note: the adult lizard in Attenborough’s clip is not a Heliobolus lugubris but is an adult Ichnotropis – a different genus of lacertids!]

Our evidence supporting mimicry was indirect but reasonably convincing. Almost three decades after our Science report, we learned that Almuth Schmidt – a grad student in Germany – was studying these lizards and beetles. Would her findings support our story? Her thesis work was eventually published as a book and later reviewed by Eric and me.

Schmidt worked in the Limpopo region of South Africa, east of the Kalahari. She made remarkable observations and conducted experiments with lizards, beetles, and snake predators. Her work strongly supports mimicry. In experiments, she showed that visually hunting snakes avoid arch-walking juveniles but will attack if juveniles stopped arch- walking and instead moved like normal lizards. Even more remarkably, the baby lizards adjusted their behavior to the type of snake they encountered. They remained immobile or arch-walked when they encountered a visually hunting snake but would run away at high speed if the snake species relied on olfaction to detect prey. Overall, Schmidt’s studies support and supplement our Science paper. Hers is one of the most comprehensive studies of mimicry we’ve seen – we admit to bias here.

Several of our subsequent trips to the Kalahari were in late summer, and we were always delighted to see baby lugubris again. In fact, I enjoyed them more than when we first guessed that they were mimics (1970).

But the story isn’t over! Although the black coloration appears to prove some protection against predators, but it might increase heat gain from solar radiation, thereby reducing activity times and possibly growth rates. In other words, this mimicry might induce a thermal “cost” as well as a survival benefit.

Susana Clusella-Trullas, an expert in the thermal consequences of animal coloration and in physiological ecology, joined us on recent trips to the Kalahari. She measured the reflectance of the skin of H. lugubris and of other baby lacertids. We will use biophysical methods to determine whether dark coloration increases rates of heat gain and thus reduces activity time and possibly growth rates of juveniles in summer months. Estimating the benefits of mimicry is one thing, but estimating the associated costs is quite another. Stay tuned.