Part four – Kalahari

Living in the Kalahari Desert through all four seasons was the seminal experience in my biological development and career. I was in the field from late November 1969 through mid-October 1970, and it was there that I became a field biologist. Moreover, the Kalahari gradually became my second home. I’m happy there.

The Kalahari project was entirely Dr. Eric Pianka’s idea. For his Ph.D. thesis, Eric had done classic research on the species diversity and ecology of desert lizards in western North America. Then as a postdoc with Robert MacArthur, Eric and his wife Helen traveled to the deserts of western Australia for well over a year. The species diversity of lizards there dwarfed what Eric had found in North America; but the outback was hardly an easy place to work. When Eric and Helen returned to the States, Eric started an Assistant Professorship at the University of Texas (fall 1968), where Larry Coons and I were students.

Given the successes of his prior studies, Eric wanted to study lizards in a third major desert, hoping to find ecological determinants of lizard species diversity that complemented those he’d documented in North America and Australia. He picked the Kalahari Desert, a temperate zone desert in southern Africa. Eric was awarded an NSF grant to fund his project.

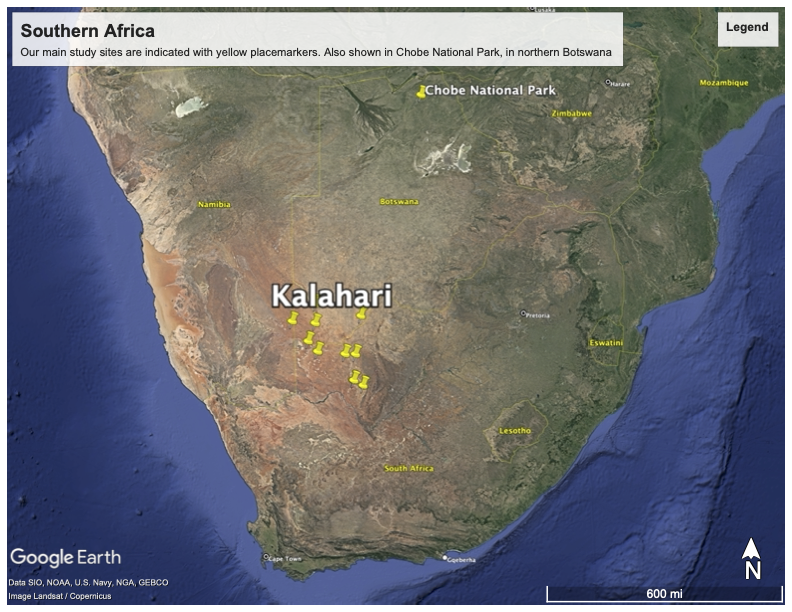

The Google Earth Image below shows the positions of our main study areas and Chobe National Park, in northern Botswana (27 Being alone). We would try to visit all of the sites each month, spending two to four days at each before moving on.

The Kalahari “Desert” is a vast sandy savanna and occupies much of Botswana, the northern part of South Africa (Northern Cape Province), and the eastern part of Namibia. The sand covers 900,000 square kilometers (350,00 square miles – much bigger than Texas at 268,596 square miles), but the arid region is limited to the southern part.

The Kalahari is called a ‘desert’ – not because of its xeric vegetation – but because of its low rainfall and porous soil. Bunch grasses and small shrubs cover much of the ground, and large acacia trees are common in some areas.

The southern Kalahari, where we worked, has two main regions. In the far west, the sands are piled into longitudinal dunes and stabilized by vegetation. To the east, the sands are flat.

In the sandridge zone, the Kalahari sands have a distinct reddish color caused by an iron oxide coating on the sand grains. However, sands found in the (usually dry) river courses are white, as erosion has worn off the oxide coating.

Photographs of magnificent and vegetation-less red dunes in the Kalahari are regularly featured in glossy travel magazines and advertisements. However, such vistas are not typical of the Kalahari and result from severe overgrazing by sheep and cattle or of 4 X 4 destruction.

As deserts go, the Kalahari is visually undramatic. It is expansive, and in some areas, its longitudinal sand dunes extend as far as one can see. But the Kalahari pales in visual comparison with the nearby Namib Desert, which lies along the southwest coast of Namibia.

But to me, the Kalahari is home. I’ve made six trips there over the decades, and I always bubble with excitement as I drive north into the Kalahari from Upington, a frontier town on the southern edge of the Kalahari. A new (paved!) “Red Dune Route” traverses the sandridge section of the desert, passes close to our Groote Aarpan site, provides rapid access to our two study sites in the Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park (a park formerly known as the Gemsbok Park), and sideways access to other study sites in the dune region.

On a table in my bedroom in Seattle is an ancient museum jar – a ‘Grandidier’ jar from Harvard’s Museum of Comparative Zoology, which sold its old jars in the early 1970s. That jar partially filled with red Kalahari sand. Laying on the sand are lion claws, which I pulled off a ‘very dead’ lion in Botswana in 1976 (with permission of the park Ranger). That jar cradles a near lifetime of memories and biology. Some of those memories are shared below.