18 A day in the life

On one of our first nights in the Kalahari, we camped on a farm along the Kuruman River. We set up the tent, ate dinner, and headed out for geckos. When rain started, we dashed back to the tent and turned off our headlamps to save the batteries.

Suddenly, we heard a scuffling on the floor of our tent. We turned on our headlamps and were startled to see a huge (gigantic, actually!) scorpion running around on our tent’s floor. We bolted out the narrow entrance of our tent, fortunately evading the scorpion. That night we slept inside the Land Rover and purchased cots on our next trip to Upington. Welcome to the Kalahari.

Over the months ahead, we saw many scorpions (large, small, yellow, black, with small pincers, big pincers, etc.). We noted that scorpion activity shot up during rainy periods. We had been warned to avoid scorpions with small pincers and big tails. These were ‘parabuthids,’ and their venom was potentially lethal to humans. We developed a mnemonic to help us distinguish parabuthids from other scorpions: any scorpion that could get by with small pincers must have nasty venom in its big tail. In any case, we did our best to avoid any scorpions.

Upon awaking at sunrise, but while still ensconced in our sleeping bags, we would open a thermos of coffee that we’d prepared the night before. We’d share (usually demolish) a box of Crumble Cream cookies for breakfast. Sadly, Crumble Creams have gone extinct.

Once we were up, ‘coffeyed,’ and ‘crumble creamed,’ we would put on our boots, gather our collecting gear (BB gun, notebook and pen, binoculars, notebook, lizard sack), and head out to the veld, usually about 8 am in summer. After collecting for several hours, we’d take a brief break to drop off specimens at Molly, drink water, and then head out again.

In summer, lizard activity slowed dramatically in the late morning heat. By 11 am or later, we’d head to the Land Rover, sit on a cot in the shade, and begin weighing, measuring, and pickling our morning’s haul.

Lunch followed and was often a can of corned beef + piccalilli + crackers. We eventually grew sick of this meal (in fact, I had several unopened and unwanted cans of corned beef in the food box at the end of the trip, and I’ve successfully avoided piccalilli ever since).

Shade at midday was worth its weight, but some shades were better than others. One midday early in the trip, we set up cots underneath a sprawling acacia tree. But when we looked down at our feet, we saw giant ticks (“taipans”) swarming towards us. We immediately fled from that shade.

Obviously, we needed to make our own shade, away from acacias. On the next trip to Upington, we bought a large blue tarp. Upon arriving at a camp, we’d attach one side of the tarp to Molly’s roof rack and suspend the opposite side on two poles, anchored by guy lines to the sand.

Now, we could weigh, measure, and pickle in shaded comfort. Then we’d eat lunch, drink a not-hot beer (Section 19.2), collapse on our cots, put a wet towel on our chests, and hope to pass out before the water evaporated. We never succeeded but we kept trying. In any case, we’d periodically have to move the cots as the shade kept moving. But we survived some sweltering days.

Larry and I tradee off cooking dinner, and Eric took his turn when he was with us. We mainly ate packaged dinners of rice & curry and always buried these with copious amounts of Mrs. Ball’s Chutney, which was cheap, wonderfully sweet, and made almost any food taste better. [Mrs. Ball’s continued to be a much loved condiment on all subsequent trips.]

Sadly, fresh meat was a rarity. We could cook meat the first evening after leaving Upington, but not after that as we lacked refrigeration. Early in the trip, a farmer in South West Africa generously gave us a whole leg of lamb (or springbok?). Larry and I had to struggle to figure out how to cook such a hunk of meat – I don’t think we had a grill then. And it was a lot of meat for two! But it was memorable.

A month or two into the trip, we discovered that we could supplement our meat ration by becoming hunters. Botswana had loaned us a .22 caliber rifle. Whenever we crossed into Botswana, we’d pick up the rifle from Customs, head to our study area south of Tsabong, and hand the rifle back a few days later before returning to South Africa.

We decided to try hunting springhare, a hippity hopping rodent that liked and behaved remarkably like an overgrown North American jackrabbit. They are nocturnal, so we’d have to hunt at night. We’d put on a headlamp, sight down the barrel, and aim at and try to shoot a springhare. Shooting this way is surprisingly tricky, as parallax with the headlight beam makes it hard to aim the rifle. Even so, we got good at this and enjoyed several springhare at this site.

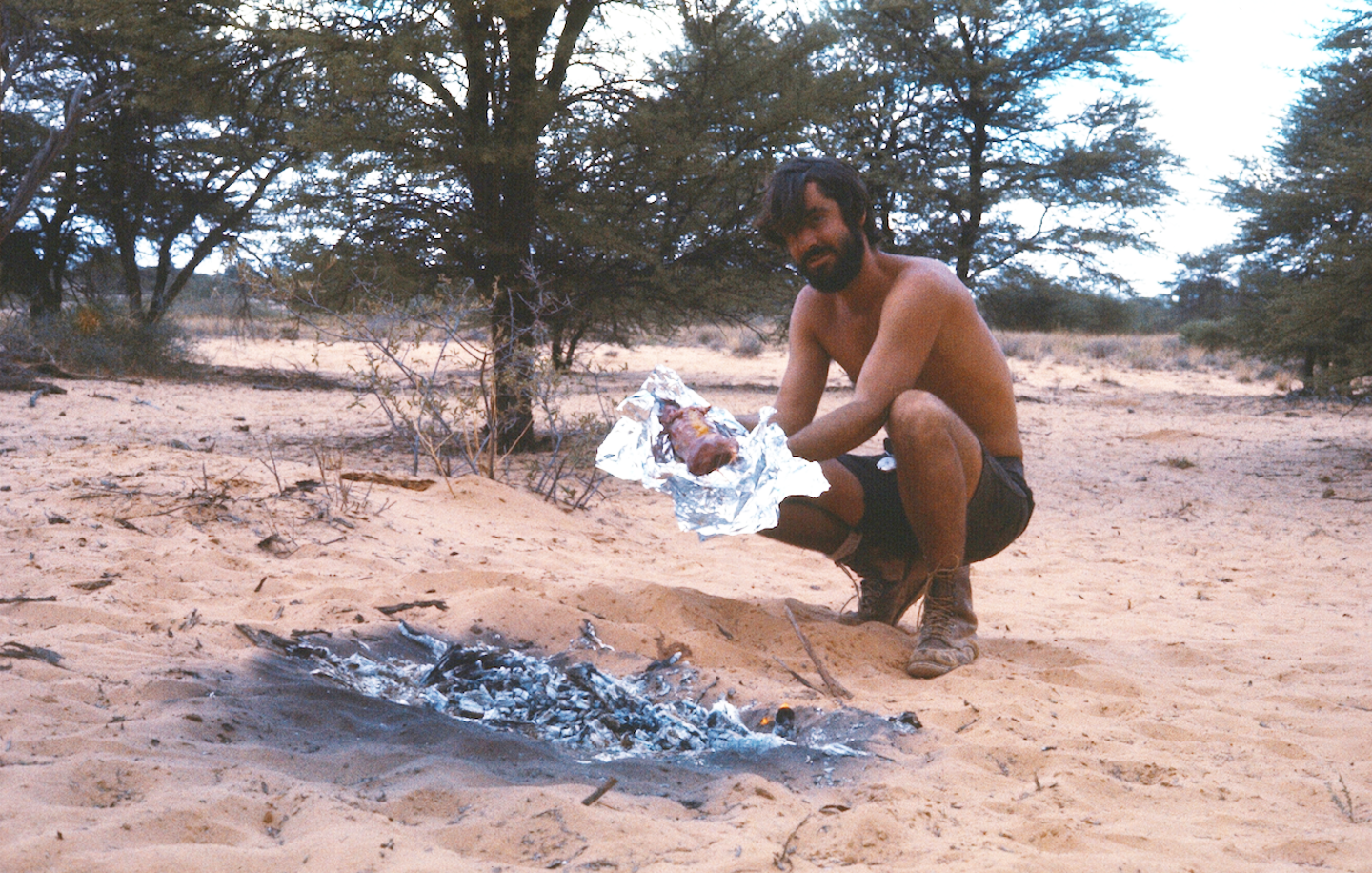

The morning after a successful hunt, we’d build an acacia fire on top of the sand, let the wood burn down to coals, scoop the coals and a bit of sand away, stuff the springhare (cleaned, of course) with peaches and pears (or whatever canned fruit was available), wrap it tightly in aluminum foil, lay it on the hot sand, put sand on top, and cover it with coals. We’d wait patiently for an hour, dig up and open the aluminum packet, and feast. This was Springhare a la Kalahari. We pronounced it good.

‘Springhare a la Kalahari’ ready for baking in a sand oven. I believe Rogue beer has gone extinct.

As the sun set, we’d sit on our cots, look out into the desert, enjoy the chorus of barking geckos, grab our headlamps, and start searching for geckos. By 10 or 11 p.m., gecko activity would drop off. We’d return to camp, have another weight, measure, and pickle session with our evening’s catch, and finally sleep. These were long days.

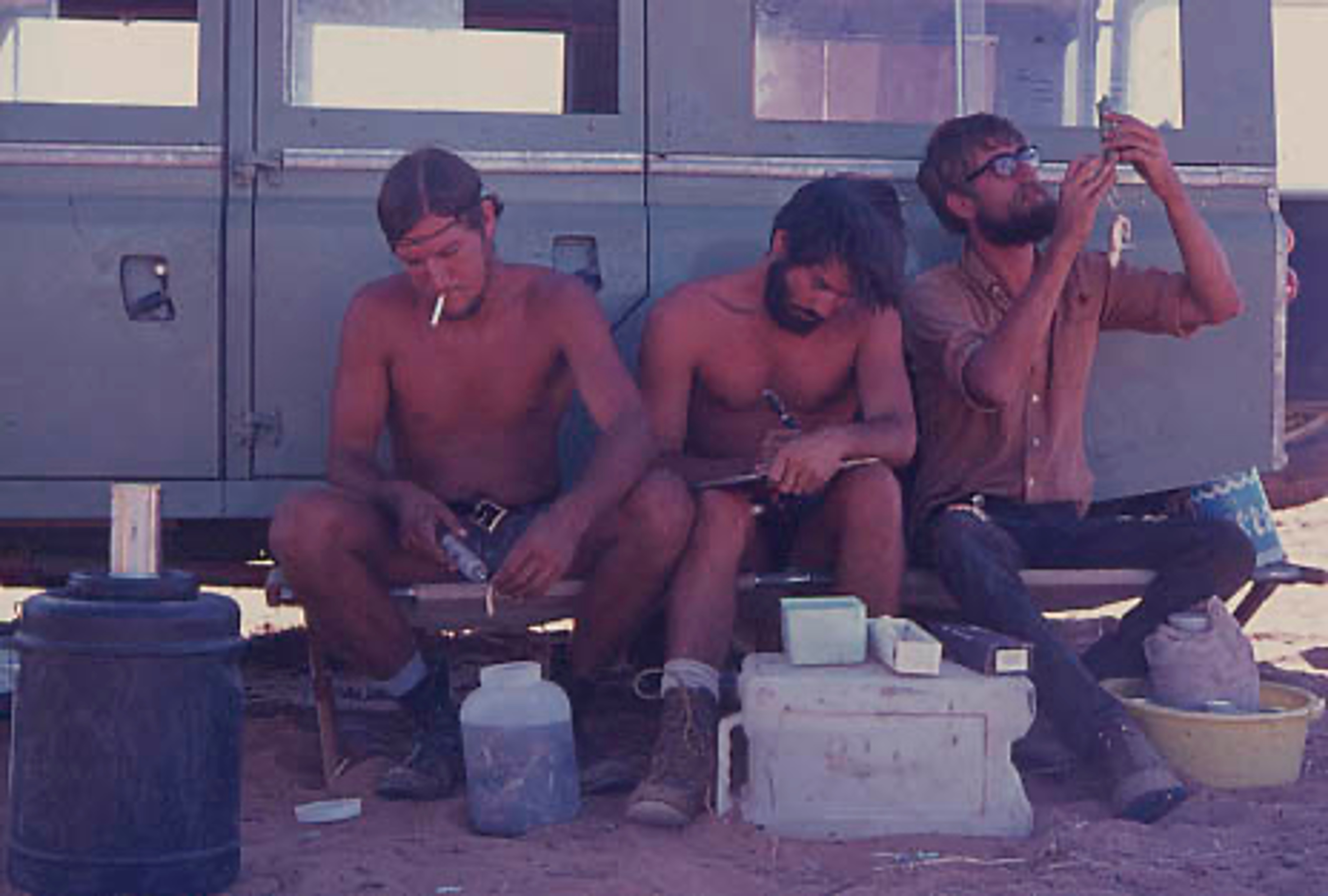

During the hot summer months, Larry and I lived in shorts (no shirts, no hat, but we did wear boots!). The Kalahari sun did permanent damage to our skin (I’ve had two skin cancers so far), but at least we didn’t have to wash clothes, as basically we weren’t wearing any. And we both smoked at the time, so we probably couldn’t smell ourselves anyway.

Every two weeks or so, Larry and I would head to Upington for a badly needed shower, supplies, food, real meals at a cafe, mail, and fresh batteries for our headlamps. Bathing was challenging in the veld, as the only shower (outside of one in Upington) on our circuit was in the Gemsbok Park. But as international representatives of American youth and culture (or the lack thereof), we felt obliged to at least take a sponge bath before venturing back to Upington for mail and supplies.

Part way through the trip, we figured a way to clean our blood-sweat-and-tears encrusted bodies. On the morning before heading to town, we’d put a 5-gal water jug on top of Molly and let it warm in the sun. We would then attach a hose to the jug’s spigot and then take a brief shower, which would wash away some of the accumulated grime. For obvious reasons, this technique did not work in winter – but sweating wasn’t an issue then.

On summer evenings in Upington, we’d sometimes sit on the bonnet of Molly (our long-wheelbase Land Rover) and watch a film at the Kalahari drive-in. After mailing letters, shopping, and packing Molly, we would head back to the veld for another two weeks.

During summer, we generally slept on cots rather than on the ground – scorpions were entirely too abundant. During cooler seasons, Larry and I slept in a two-person tent (with a fabric floor) made by Blacks of Scotland. This tent was our home. It wasn’t spacious, but the sand beneath the tent floor made for a comfortable mattress. Fortunately, neither of us snored – at least then.

Our tent did blow over one night in a wicked windstorm at our R area. After a sleepy moment or two, Larry and I decided not to fight the wind, and we eventually fell back to sleep with the collapsed tent flapping in our faces. I loved the noise and chaos of that stormy night. Upon arriving in Upington, we’d immediately head to a campground on the Oranje River and take a real shower before venturing into town. We used a cold shower for months before we discovered a hot one in a different section of the campground. Joy to the world! Despite our efforts to get clean before shopping in Upington, I rather suspect that the locals still thought we were dirty hippies.

Life in wintertime was very different. Indeed, the livin’ was easy. Days were short, and the lizards ‘lay low.’ Most of the time I was alone (Chapter 27) and could hunt lizards only when the weather was favorable. But many winter days were cold, overcast, and windy – no point in looking for lizards. Furthermore, barking geckos were silent, and other geckos were inactive. Thus, my lizard hunting in winter was often limited to just a few hours (if that) at midday. What a change from summer!

I had more free time than I’d ever had in my adult life. I spent most days in the tent (or in Molly) reading, teaching myself calculus, or attempting to sketch. I was never bored – in fact, I was a very happy camper.

Winter mornings still started off with coffee and Crumble Cream cookies. Although our trick of preparing a thermos of coffee the night before worked well in summer, it failed in winter. The nights were just too long and cold (often near freezing), so my coffee would be lukewarm by sunrise. One solution would be to heat water on my Primus when I first awoke. But at sunrise, that was too much work. I derived a simple solution. I’d still make a thermos the night before, but now I’d bury it in a sack in the sand and then pull it up the next morning. Sand was a good insulator, and my morning coffee remained hot and accompanied my meal of Crumble Creams. Not a very nutritious way to start the day, but I liked it – and did so until I left the Kalahari.