59 A non-parent studying baby names?

The most fun I have as a scientist often happens when I come up with a wild and crazy idea. Such ideas usually pop up when I think about merging topics that are traditionally viewed as academically separate. One example involved my analyzing the success and death rates of Himalayan mountaineers: here, I applied statistical techniques from evolutionary studies and applied them to Himalayan mountaineers. But undoubtedly, my wildest and craziest idea came about when I started thinking about baby names.

What, baby names? I concede that I was a baby once and was given the name “Raymond.” But I never became a parent and have rarely wanted to be one. I usually avoid babies and young children. I once had to spend two months with a 2 ½ -year old – that experience cauterized any latent desire to become a parent.

Why did I become interested in baby names? I remember when it happened, but not why it happened. I was at a Gordon Conference in Maine around 2008. These conferences focus on a particular theme, and this one was on The Metabolic Theory of Ecology – a hot but hotly debated topic. Afternoons were largely open, but we were encouraged to meet and talk with other participants. But one afternoon, I needed a break and retreated to my dorm room, hoping to check email and be alone.

I started wondering about baby names, explicitly wondering why some girls are named April, May, and June but rarely after other months. Why I started thinking about month names is wiped from my memory. Perhaps one of the women at the conference was named April or I saw the name June on the internet. I don’t remember.

In any case, once I thought about these names, I realized that April, May, and June are spring months, at least in the Northern Hemisphere. Parents may select those names because spring is a season of rebirth and growth, and baby girls symbolize the birth of a new generation.

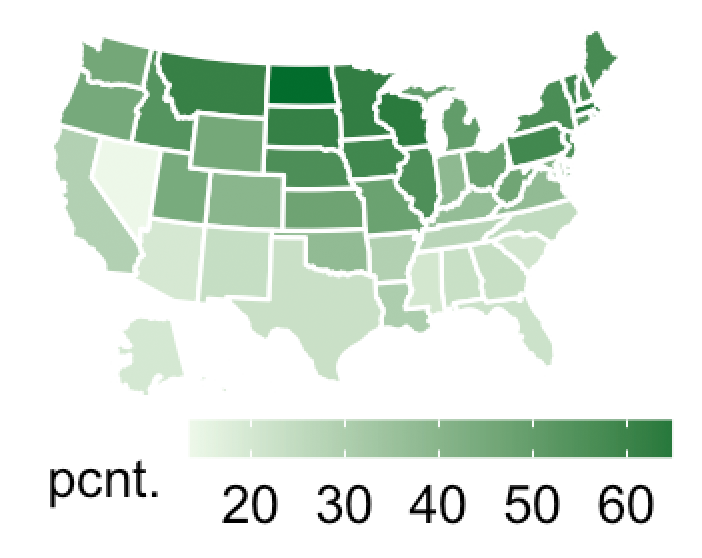

Suddenly, my thoughts leaped through several steps. Possibly because the conference was in New England, a highly seasonal region, I thought that spring arrives relatively late in northern states but much earlier in southern ones. If parents are naming their daughters after months that symbolize spring, new birth, etc., then the relative popularity of these month names should vary with latitude. Specifically, June should be the most popular month name in the north, whereas April should be the most popular month name in the south. After all, April in New England is still essentially winter! That was indeed a wild and crazy idea. I enjoyed this speculation, I had no idea whether name data were even available for study, so I dropped the project off my radar.

Some years later, I happened across an R package called “Baby names.” Hadley Wickham, a leading R programmer, had compiled name data from the Social Security Administration of the US government, which publishes name data every year (at least names of those who receive a social security number). This data set and has been analyzed from diverse perspectives. The online version has the number of new babies with each given name for each state and year (from 1910 on). Soon I discovered a related R package (“Oz baby names”), which compiled name data for Australia.

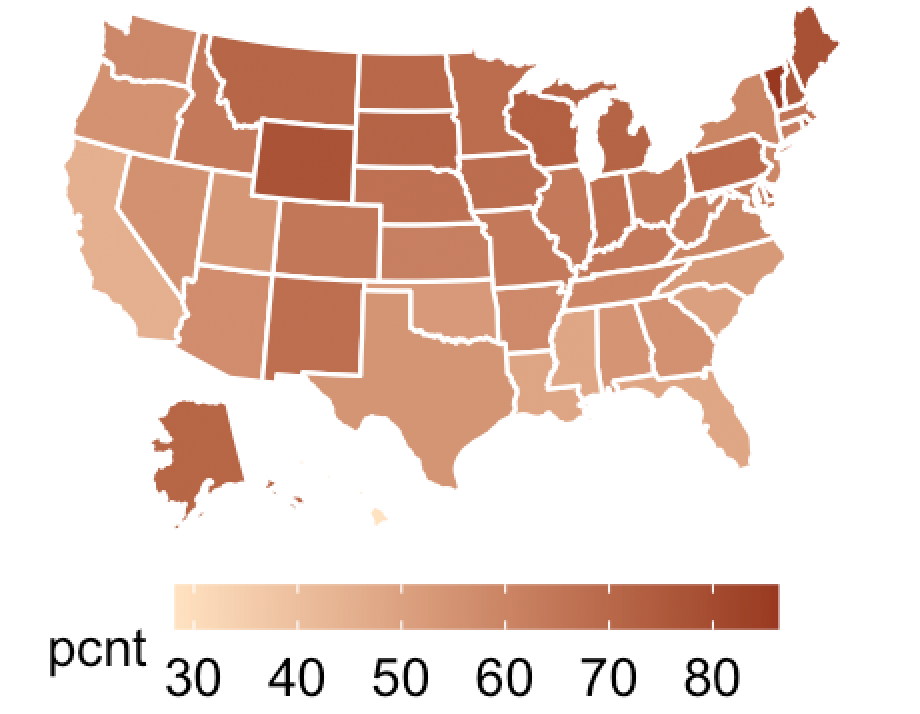

I downloaded the massive data and focused on the number of girls with spring-month names. For each state, I computed the percentage of girls named April (or May or June) and plotted these on a ‘choropleth’ map.

I couldn’t believe my eyes. In the north, June was indeed the most common month name, whereas in the south, April was predominant. My expectations held, and the pattern was strong.

Buoyed by that unexpected success, I thought next about season names (e.g., Summer, Winter, Spring, Autumn/Fall). No girl in the data set is named “Fall,” for obvious reasons. But Autumn and Summer are popular names. I’d lived in New England as a graduate student and loved the radiant colors of foliage in Autumn. Consequently, I guessed that Autumn would be most common in states with many deciduous trees. I found data on relative intensity of Autumn leaf colors for 31 states, and the relative frequency of Autumn was highest in the northerns atates and positively correlated with the intensity of fall coloration, as I predicted!

I could have run a statistical correlation of the percentage of girls named April versus latitude (or of Autumn versus intensity of foliage coloration) of each state. However, I knew that a correlation analysis would be statistically invalid, as nearby states were not independent – and such independence is a central requirement of traditional correlation analyses. I knew that Don “Naja” Miles could analyze spatial data. We share many biological interests in common, and Miles is a first-rate statistician to boot. I was delighted when he agreed to help.

We wrote a paper that quantified geographic patterns of month names, and added information for Canada, the UK, Australia, and New Zealand. By large, the geographic patterns beautifully matched our expectations. We were excited by the patterns and assumed that they would also interest to a wide audience, given that everyone starts life as a baby and that most babies eventually become parents and must choose a name for their babies. Consequently, we thought, let’s submit to a top journal. Colleagues who had heard about our study were enthusiastically supportive.

Sad story – here’s a short version. We first contacted the Editors at Science, asking for a pre-submission review, given the ’off-topic” theme of our paper. Science delined to have it reviewed. Next, our manuscript was rejected without review by a succession of five – count ’em five – more journals. Miles and I were disappointed and irritated, if only because reformatting for each journal was a waste of time and effort. Moreover, we liked our paper.

Manuscript rejection is a normal part of academic life – at least when one is trying to publish in top journals. But repeated rejection had happened only once to me before when several of us tried to publish a manuscript analyzing the effects of age and gender on success rates and death rates of Everest mountaineers. That manuscript was also rejected six times without review.

Two factors might explain such repeated rejections: 1) the papers and analyses were uninteresting or weak, or 2) the topics were too novel to fit in traditional (conservative) academic journals – they just fell into a crack. Of course, I always favored the second explanation.

After the Everest paper was rejected for the sixth time, I knew I needed to change my approach. Previously, I’d submitted each version via normal channels. And in my cover letter to the Editor, I had never mentioned the prior rejections. Had I done so, the Editor’s first impression – even before reading the paper – would assume that this paper must be flawed. Instead, I decided to write directly to Brian Charlesworth, Editor of Biology Letters, a relatively new but prestigious journal from the Royal Society. Brian is a premier evolutionary geneticist, and we had met briefly in Chicago a few years before. I told Brian the long and gory history of rejection and said that I wanted to submit to Biology Letters but would do so only if he felt the paper might fit within the domain of the journal. He wrote back, saying the paper sounded interesting, and encouraged me to submit it. I did. The paper received positive reviews and was published. Relief.

With baby names, I felt back in this same ‘rejection without review’ treadmill. Eventually, I decided to write to Mark Pagel. Initially, Mark developed statistical methods for comparative biology but switched to studying the evolution of human languages. I knew tht Mark would understand the concept of the baby names paper and hoped he could recommend some ‘human biology’ journals that might be welcoming.

Mark suggested that consider a new journal (Evolutionary Human Sciences) published by Cambridge University Press). Ruth Mace was the Editor and Mark’s wife. Importantly, Ruth’s journal had already published papers on baby names. Ruth contacted me and encouraged us to submit. We did. The paper got strong review and was published. A second “phew.”

Recall that Science rejected the baby names paper after an internal (but not ad hoc) review. Miles gave a talk on our baby names project at the annual meeting of the Society for Integrative and Comparative Biology. Elizabeth Pennisi – a highly respected journalist and Senior Correspondent for Science – heard his talk and asked if she could write a news report about it for Science. We of course agreed, and Liz published a delightful review after our paper was eventually published. Thus, we eventually got in Science, but not quite how we intended or expected!

What is the lesson here? Well, trying to publish off-the-wall projects (Everest mountaineering, baby names) will often be challenging. My suspicion is that journal editors sometimes conservative by nature and unwilling to publish unconventional studies. Alternatively, perhaps I overestimated the appeal of these papers. Neither explanation is exclusive.

Will these experiences induce me to stop doing off-the-wall projects? I hope not. I have enjoyed doing such studies (Everest climbers, baby names, paleo-mountaineers) more than most of my studies on lizards and flies. On balance, that fun more than balances the irritation of repeated rejection. But when I do another off-the-wall project, I will go directly to the Editor (rather than submit through traditional channels) and try to make a strong case why journal X should review my paper.

One final comment on publishing strategy. Early in my career, I submitted a paper to the top herpetological journal. My paper was reviewed by herpetologists – real herpetologists who obviously knew and loved everything about herps. They raised many minor (at least to me) issues and complaints, and the Editor rejected my paper. Should I next submit to a lower-tier herp journal? I decided no, as the reviewers would still be dedicated herpers – perhaps even more dedicated. Consequently, I submitted my paper to Ecology, a more general and prestigious journal. The resulting reviews were positive, and my paper was accepted.

Perhaps this experience reflects the Law of Small Sample sizes. But I suspect reviewers for specialty journals focus excessively on details and are less intested in conceptual perspectives. They focus on twigs, not forests.

Rule of thumb: when a paper is rejected by a specialty journal, and if the reviews seem excessively picky, consider submitting next to a more general journal. This strategy has worked for me on more than one occasion.