5 Deep Springs

I had just turned 17 when I arrived at Deep Springs College in September 1961. Summer was ending, and the Valley was dry and bleak. I remember thinking, “What have I gotten myself into?”

Like most Deep Springers, I’d skipped my senior year in high school. I joined three classmates, plus a one-year visitor from Cornell. Second and third year students were already there, and the total student body included about 20 students.

Interactions at Deep Springs were often intense, as we all lived together and had no outside social contacts. Lincoln Bergman soon became my closest friend. We had come from polar opposite backgrounds but nonetheless resonated. Many an evening we walked around the ranch or out in the desert, discussing whatever. Encounters with Lincoln opened up new worlds for me.

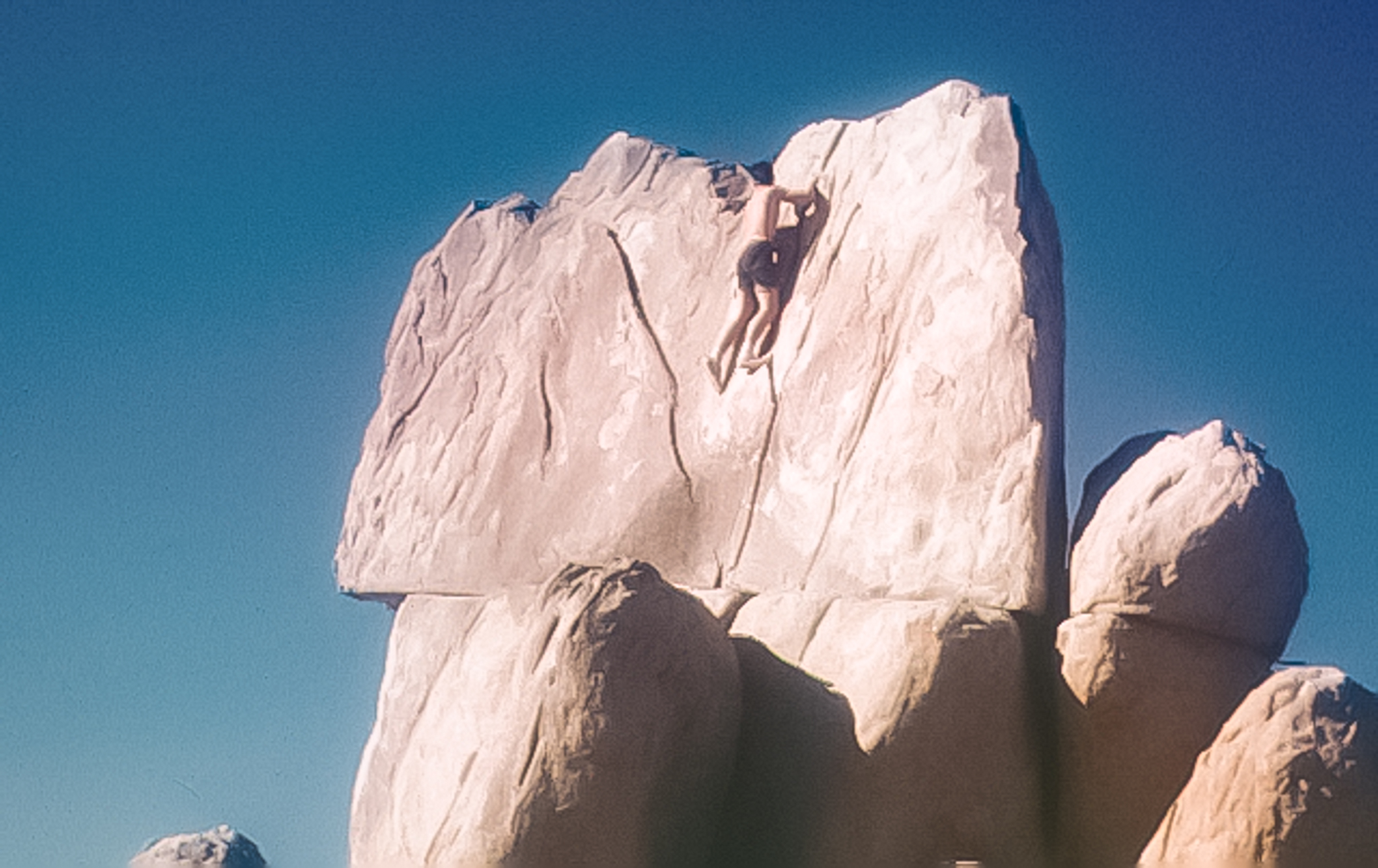

I sometimes loved – I sometimes hated – Deep Springs. I loved the high desert, and the White Mountains and in the eastern escarpment of the Sierra Nevada offered hiking and climbing enticements. I thrived on the hard physical work of the labor program, which was an integral part of Deep Springs. Moreover, I liked the small classes, even though not all were particularly useful or well taught.

The challenges came from the intensity of interactions combined with social isolation. We lived together in a tiny community 24-7. We had no distractions (no TV and no internet) and no escapes – only ourselves, the ranch, our Valley, and the mountains.

Tensions built over the academic year, resulting in the “annual spring crisis.” I had had a sheltered childhood, and I was surprised and disturbed to witness the political maneuverings of some students and faculty. However, thanks to support from Lincoln and Phil Craven, I stuck it out. I’m glad I did.

For me, the best aspect of Deep Springs was the expectation that we – still very young students – were responsible for ourselves, the ranch, and even the College. In exercising that responsibility, we grew up quickly, often without realizing it.

Many Deep Springers had special talents – in class, in the studio, at the piano, in the garage, or on horseback. Usually by example and sometimes by suggestion, they encouraged me to try new things. I attempted painting, sculpture, and even piano (see Chapter 60). I never excelled at these arts, but trying them was exciting and liberating. I enjoyed associating with people who were skilled and excited about whatever they were doing. Their enthusiasm rubbed off, even when their skills did not.

Deep Springs did not have a summer session when I arrived, and thus, a few students needed to stay and keep the ranch going through the summer. At the end of my first year, I volunteered to stay for the first half the summer. Three of us regularly worked 16 hours/day, 7 days/week. I hand milked cows (twice/day), fed chickens and cows, irrigated alfalfa fields, bucked hay bales, did laundry, watered and mowed lawns, and tried to repair whatever needed to be repaired. The work was physically demanding but immensely rewarding. We slept well.

We were paid the prevailing minimum wage ($1.15/hr), but for a token of one hour per day! My first paycheck totaled about $30. I have never enjoyed spending a paycheck more (I bought a nylon lariat, which I still have).

The following summer, Deep Springs initiated a summer program of classes, thereby enabling students to graduate after two rather than three years (assuming they stayed for two summers out of three). A few of us volunteered to help the incoming first-year students get settled. I loved the opportunity of spending another summer in the Valley.

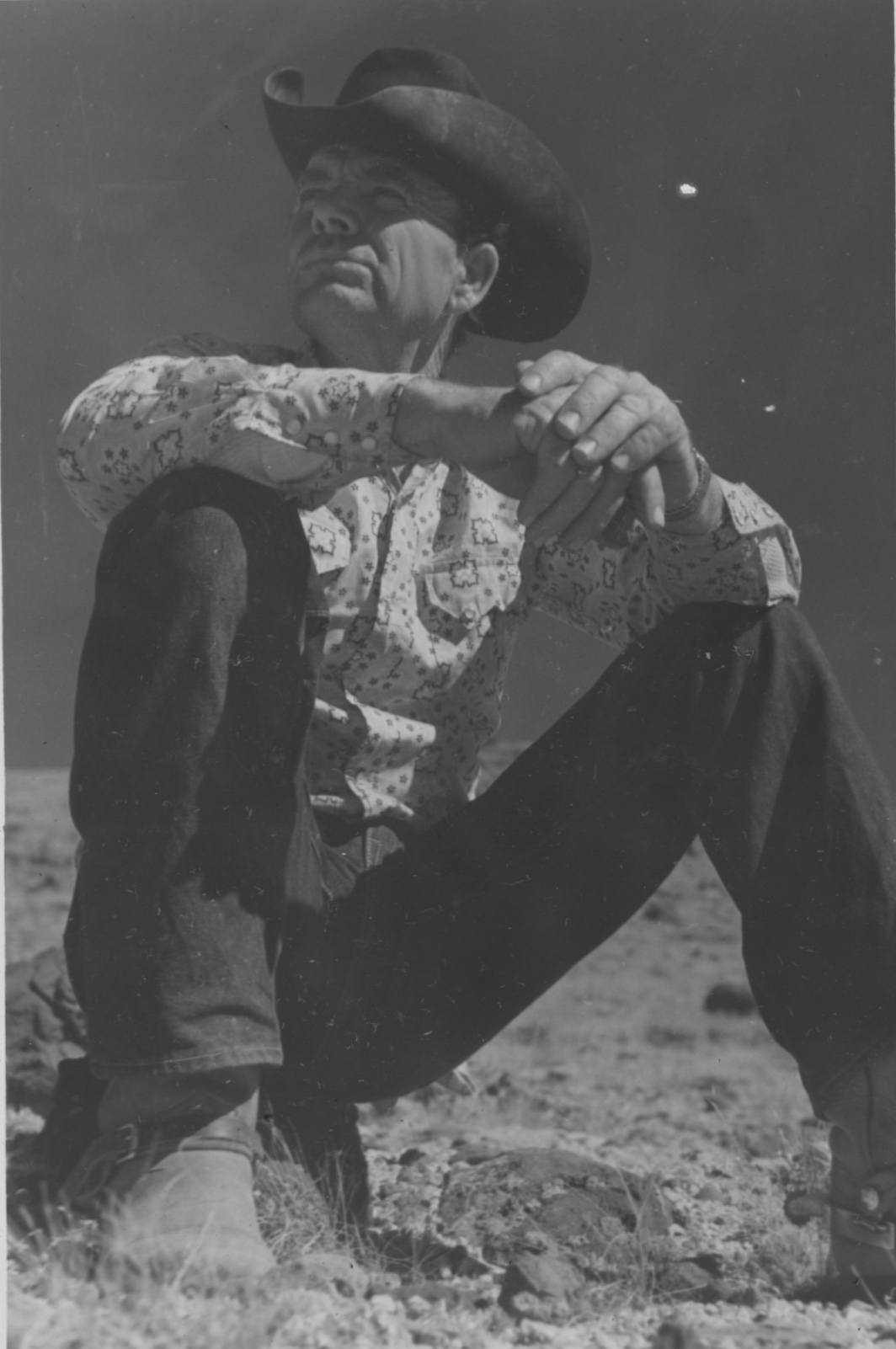

Deep Springs was more than its students and faculty. Fogger Dunagan and then Frank Poole were archetypal cowboys. They got things done and could out-think all of the students in an emergency. Our chefs (especially the Rockstrums and Warren Jacober) taught me to love cooking and food. James Martin (a revisionist history professor) introduced me to classical music and early jazz. Several of us often spent the evening in his cottage, studying while listening to his extraordinary record (LPs and 78s) collection, which included Bach to Jelly Roll Morton to Schubert and beyond. I watched Doc Martin write and edit a book on anarchism and learned how much dedication and persistence go into academic projects. [At the time, I had no inkling that he was a Holocaust denier.]

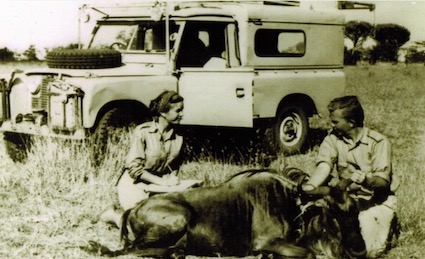

Some memorable encounters came from short-term visitors. Lee Merriam Talbot and his wife Marty came through. Lee had been a Deep Springs student (class of ’52). He gave a talk about the ecology of wildebeest in east Africa, based on fieldwork he and Marty had recently done for his Ph.D.

Lee’s lecture was my first formal introduction to ecology. I loved their story, both the African adventure and the conceptual aspects involving ecological interactions. I didn’t realize until years later how much that lecture – combined with my living in the desert of Deep Springs – were my first nudges toward a career in biology.

Lee went on to become an international leader in conservation: he was the principal architect of the Endangered Species Act (ESA), the Marine Mammal Protection Act (MMPA), and the Convention on Trade of Endangered Species (CITES). While a student at Deep Springs, he helped open a new climbing route on the east face of Mt. Whitney and later became an accomplished race car driver. Marty worked extensively in international conservation initiatives. What a couple! Their visit was memorable and inspiring.

The cattle roundup was the event of the year. We would herd hundreds of cows and their calves into a rock-walled corral. Then we would rope the calves, toss, brand, de-horn, and castrate them as appropriate. This was hard, dusty, smelly, and somewhat hazardous work, but I loved it. We were transient cowboys – or at least we pretended that we were.

At my first roundup, Phil Craven was riding a big palomino named Goldie inside one of the rock corrals when he accidentally dropped one of the reins. When Goldie stepped on that rein, she could not lift her head. Suddenly, she started bucking wildly. We all (presumably bright young men) stood immobilized. But Fogger immediately ran to close a gate so Goldie couldn not bolt and yelled at Phil, “Hold onto your reins!” It was a learning moment, and Fogger’s advice seemed and was broadly applicable. It helped me hold onto my reins during emotional rough spots later in college.

By the end of the fall quarter (year 2 1/2), a classmate (Con Van Arsdall) and I had accumulated enough credits to transfer to UC Berkeley. We started there in January 1964. Mainly because I had swapped my senior year in high school for the social isolation at Deep Springs, Berkeley was a social, cultural, political, and educational shock. I had a lot of catching up to do, but the intensity and self-righteousness of Berkeley in the mid-60s made that relatively easy and wildly exciting. Berkeley was – or so we thought – the creative center of the universe. What an abrupt change from the ‘monastic’ life I had lived in Deep Springs!

Looking back, am I glad I chose to go to Deep Springs? Yes, absolutely. Life at Deep Springs was intense and sometimes challenging but strongly positive for me overall. Sustained immersion with interesting and bright people changes lives. I will share a few of these experiences in the following sketches.