8 Playing cowboy

The ranch staff at Deep Springs included a ranch manager, a cook, a mechanic, and a cowboy. Of that group, students usually held the cowboy in highest esteem (except, perhaps, when Chef was in residence). Deep Springs was a working ranch and ran roughly 500 head of cattle.

To us, cowboys were masters of three skills: riding, roping, and smoking. If we were to become apprentice cowboys, we needed to learn these skills, except for smoking, which was then banned at Deep Springs.

The legendary Fogger Dunagan and Frank Poole were the two cowboys during my time at Deep Springs. Fogger could outdo any Marlborough Man. We were in awe of him.

I was pre-adapted to becoming a cowboy at Deep Springs as I’d started riding horses as a toddler. But only some third year students got a chance to be the student cowboy – so I’d have to wait my turn and hope.

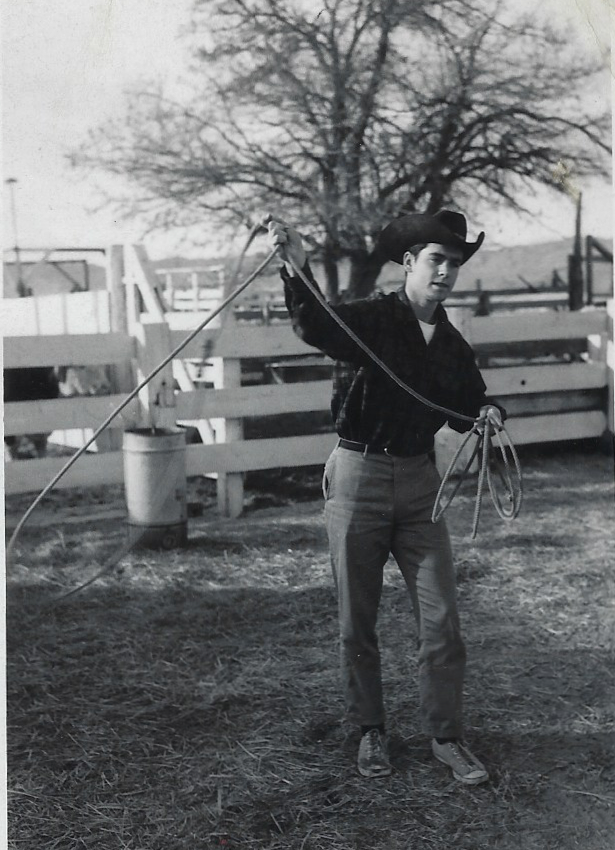

I took up roping in my second year. I practiced roping a stool on the front lawn. I practiced a lot. Roping was a active physical skill and also served as a needed diversion from social isolation.

Professor Meeker was the English professor in my second year. Once when I was practicing roping, one his kids (perhaps age 4) walked over asked what I was doing. I snapped back that I was roping a chair. The boy looked at me and said, “Ray, that’s a stool, not a chair.” I went back to roping. Being corrected by a 4-year- old was embarrassing.

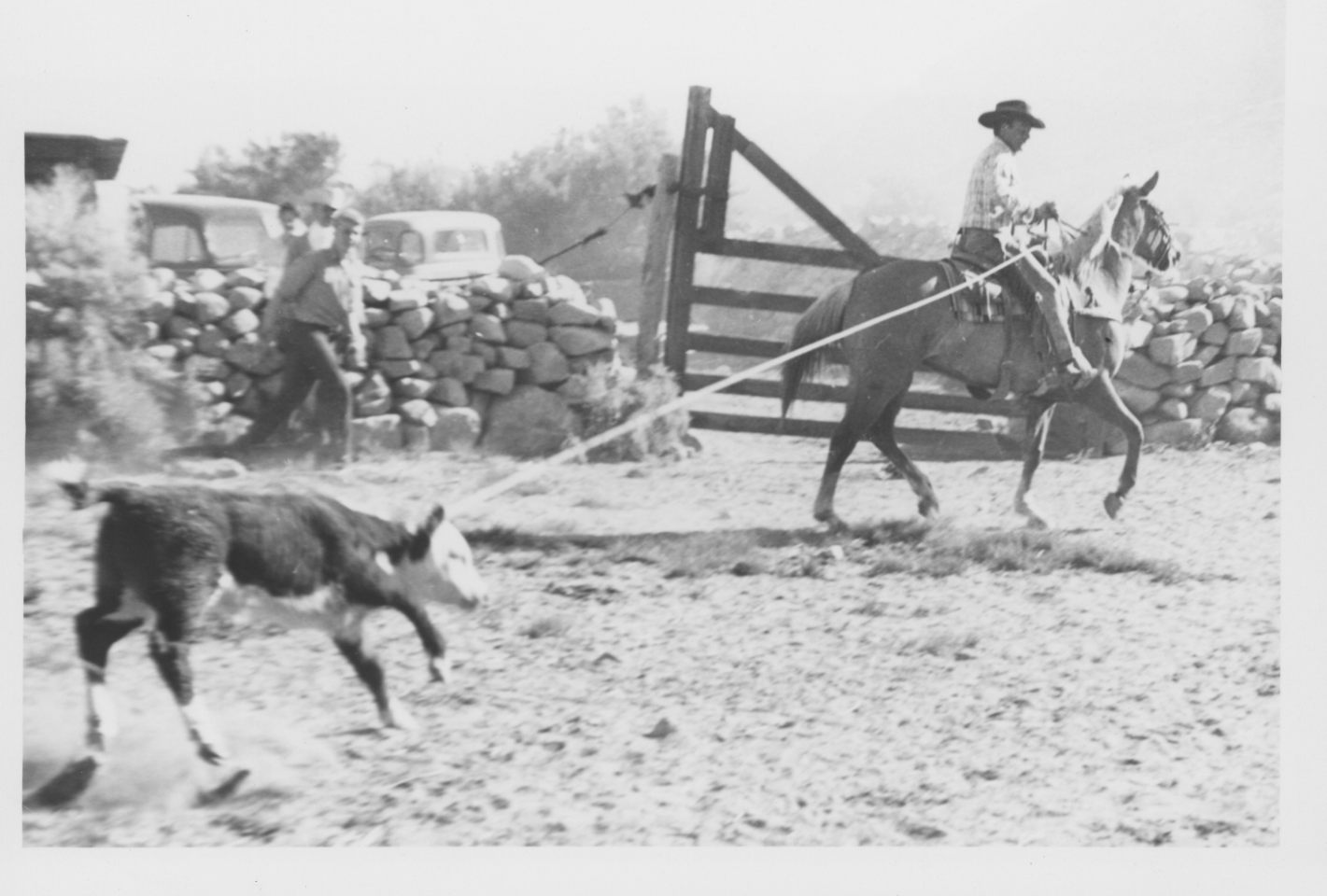

Fogger was a skilled roper (see photo below). One afternoon, a bunch of us were horsing around in the big circular lawn in front of the main building. When Fogger drove up in his jeep, we started kidding him about his roping skills.

I had been a gymnast in high school and decided to have some fun with Fogger. I bet that he couldn’t rope me as I ran across the front lawn. Fogger took the bet.

My plan was to run, and then as soon as I saw him throw the rope, I’d jump high into a tuck position and do a dive front roll onto the grass. This was a skill I’d mastered in gymnastics. I was confident that once the rope was en route, Fogger couldn’t adjust to having his ‘target’ suddenly switch from an upright runner to an elevated and tightly tucked ball.

To my complete surprise, Fogger’s lariat surrounded me in mid-tuck. He pulled tight, and I did a tucked face-plant on the lawn. Real cowboys can defy the laws of physics.

“What’s in a name?” Fogger was a nickname, of course, and it doesn’t take much imagination to guess how he got that name. When he was a young boy, a friend of his father supposedly called him a “little Fogger” (or more likely, a vulgar variation thereof).

Having mastered roping stools, I wanted to try my new skills at the annual spring roundup, which was the major ranch event of the year. We assembled all the cows and their calves in a big rock-walled corral, roped and tossed the calves, and then branded, de-horned, and castrated them as appropriate. Roundups were exciting, hard work, sometimes dangerous, and decidedly dusty. The acrid smell of branded hair and flesh penetrated our noses and clothes. Eventually the smell washed away from us and our clothes, but the smell itself is etched in memory.

I was good at roping calves from the ground. I’d rope and secure the calf until two other students tossed it and went to work. In my second year, I decided I was qualified to graduate to roping from a horse – this would be a critical step towards my becoming an apprentice cowboy. Fogger was supportive and told me to ride one of the ranch horses (not a student body horse).

In the days leading up to the roundup, I’d pre-visualized the whole process. Ride up to a calf, toss a rope around its neck, and “dally” the rope around the pommel on the front of the saddle (keeping my thump up so it didn’t get pinched and possibly amputated when the rope tightened). With the calf now secured, I’d ride forward while dragging the calf directly behind me (see photo of Fogger with a calf, above). Two fellow students would catch and toss the calf, etc.

In my mental rehearsals, I failed to consider the interval between dallying and tossing. But when I roped my first calf, it started running back down my right side, as I’d expected. But then it unexpectedly circled directly behind me and to my left, pulling hard on the rope. Now I was sitting on the horse, with a rope running over my right hip, around my back, pulling me sideways and off the left side of the horse. This was not in my plan. That calf was supposed to run directly behind me and stay there until I dragged it towards my fellow students. The calf pulled hard, and I was being pulled off the horse. But remembering junior-high geometry, I reasoned that if I (and my horse) accelerated straight ahead, we’d reduce the angle and thus reduce the pull to my left side, hopefully enabling me to stay on the horse.

So I gave my horse a hard kick, expecting it (like the student body horses I was used to riding; see below) to move forward slowly and reluctantly. However, this was a trained horse; it responded to my kick by taking off at high speed, running directly at the tall rock wall of the corral. Roping was not going as planned.

Instantly I considered the three possible outcomes: 1. The horse could try to jump the fence, with me hanging down the left side of the horse – I didn’t like that outcome, 2. The horse could turn sharp right just before the wall, which would likely smash me against the rock wall – I didn’t like this outcome either, or 3. The horse could turn left, which would push me against the horse and perhaps cause me to fall underneath its hooves – yet another unappealing outcome.

At that point, I quickly derived and chose option 4, which was to bail off the horse immediately. I knew I could rely on my gymnastics training and do a dive front roll to the ground below. If I don’t say so myself, I executed that move exceptionally well and would have earned high scores from gymnastics judges. But there was one flaw – I rolled over a fresh cow turd (recall, there were lots of cows and calves swirling about in the corral). My then black pate suddenly gained a green stripe.

Fogger watched all this, saw I was unhurt, and started laughing – no sympathy for the incompetent. The roundup continued. If I did any more roping that day, I’m sure I did it from the ground. I’d learned my limits. “Mammas, don’t let your babies grow up to be cowboys.”

Frank Poole took over as the cowboy after Fogger left. Frank was visually and verbally far less charismatic than Fogger. He was scruffy, lanky, and rarely spoke. But Frank was a skilled cowboy and generous fellow to boot. He and his horse moved like a fused dancer, and he could somehow roll a cigarette (not banned for staff) with one hand while riding a horse.

I was the student cowboy (the most highly prized labor assignment!) in my last term (fall 1963), and I spent time with Frank. One morning, we were down by the barn. Two other students ambled up and planned go for a ride on the horses that were always reserved for students (thus not “ranch” horses). One of the students complained that the student-body horses were lazy and asked Frank if he could ride one of the ranch’s working horses. Frank quietly responded that at least one of the student-body horses was pretty good.

The student objected and claimed that both student body horses were dimwitted, lazy, and unresponsive. Rather than argue, Frank decided that a demonstration was the best way to resolve this issue. Without saying a word, he mounted one of the student-body horses. Immediately, the horse’s ears jerked up. The horse hesitated for a second or two and then started bucking wildly. Frank rode it easily until the horse calmed down. Then it began following Frank’s “riding instructions” attentively. It was a very good horse, at least when it had a good rider.

Somehow, that horse knew that Frank was a real cowboy. As far as I can recall, Frank hadn’t done anything other than mount the horse and sit on the saddle. But that horse knew. The skill behind a skill is not always obvious.